by Jack Martin Leith

![]() Creating alone.

Creating alone.

![]() Creating together.

Creating together.

![]() Helping others create, in an enabling role such as facilitator, coach or thinking partner.

Helping others create, in an enabling role such as facilitator, coach or thinking partner.

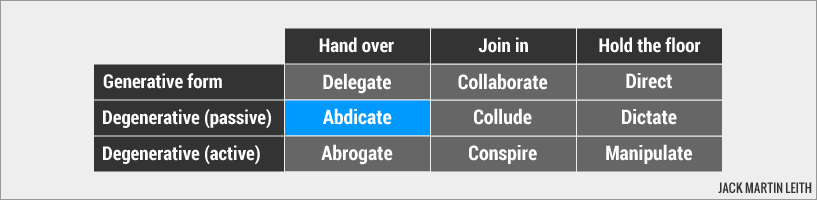

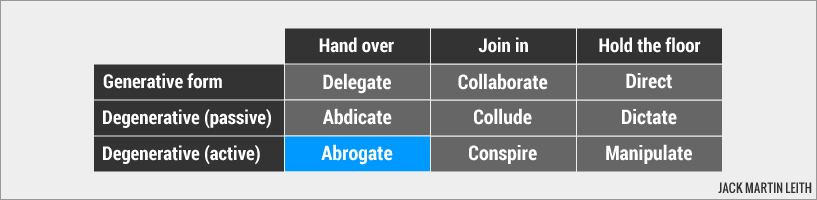

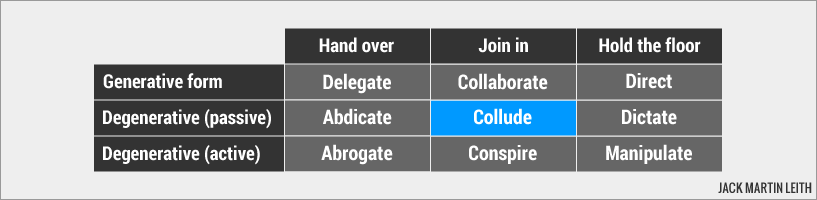

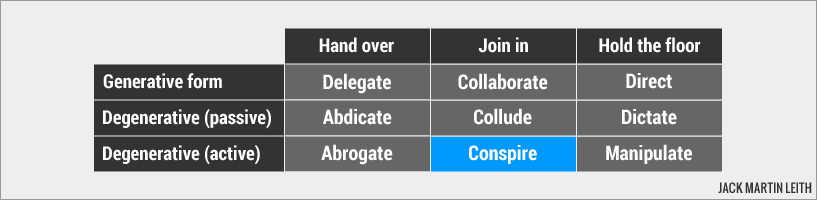

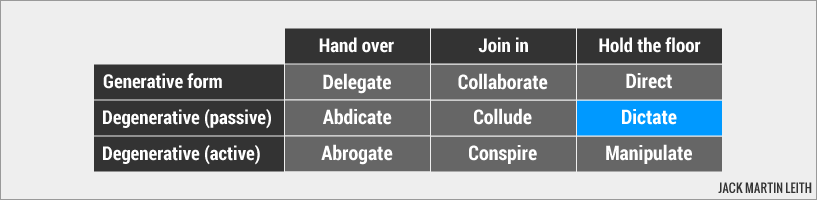

The consequences of deploying each way of working can be either generative (aimed at maximising the amount of value that will be generated downstream) or degenerative (aimed at diminishing or nullifying potential value, or generating anti-value). Degenerative consequences are often unconscious and unintended.

“Man doesn’t move between good and evil,” he said in a hilariously rhetorical tone, grabbing the salt and pepper shakers in both hands. “His true movement is between negativeness and positiveness.

Don Juan Matus, as told by Carlos Castaneda in Tales of Power | View this passage in context

This article is long and intricate, so I have summarised the main points below.

When creating alone

![]() Remember the Jacopo da Pontormo story.

Remember the Jacopo da Pontormo story.

![]() Bring in a coach to support you in your solo work.

Bring in a coach to support you in your solo work.

![]() Form a team to help you mature your concept, bring it to life and realise its value generation potential.

Form a team to help you mature your concept, bring it to life and realise its value generation potential.

When creating together

![]() Adopt practices that enable people to work alone, in pairs and in groups.

Adopt practices that enable people to work alone, in pairs and in groups.

![]() Know how to combine the three kinds of create-the-new work.

Know how to combine the three kinds of create-the-new work.

![]() Bring in a coach or a facilitator to support the collaborative work.

Bring in a coach or a facilitator to support the collaborative work.

When helping others create

![]() Make sure you are equally strong in all three enablement modes: hand over, join in, and hold the floor.

Make sure you are equally strong in all three enablement modes: hand over, join in, and hold the floor.

![]() Become adept at moving fluidly between enablement modes.

Become adept at moving fluidly between enablement modes.

![]() Maintain vigilance to avoid slipping into the degenerative forms of the modes.

Maintain vigilance to avoid slipping into the degenerative forms of the modes.

How this article is structured

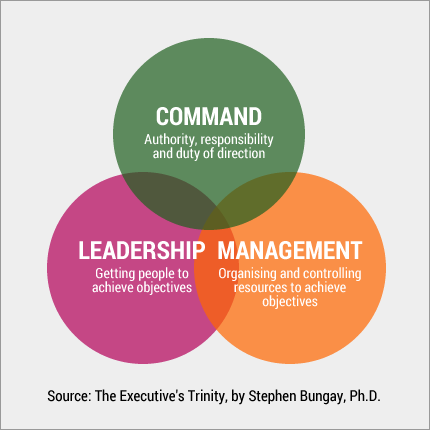

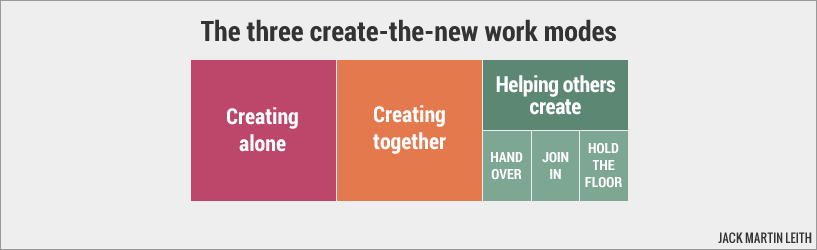

In the first part of the article, I will explain how I arrived at the three modes — create alone, create together and help others create — and I will say why all three modes should be employed when creating the new.

In the second part, I will describe the generative and degenerative aspects of each mode, as well as the three modes of enablement.

But before doing any of that, we must give some serious thought to the concept of power.

What is power?

According to Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary, power is:

- The capability of doing or accomplishing something.

- The possession of control or command over others.

Definitions sourced via The Free Dictionary.

Robert Linthicum is the founder of Partners in Urban Transformation, a US-based Christian ministry dedicated to empowering urban churches and communities. In his essay What is Power, and How Can It Be Used for the Common Good? he states that power is the capacity, the ability, and the willingness to act.An analogy: The car parked outside your house represents capacity or latent power. You are able to drive it, and you are willing to deploy that ability in order to ferry your teenage daughter into town.

Capacity, ability and willingness are prerequisites for effective action, which can be deployed for generative or degenerative purposes. In this article, I will use the term capability to encompass the three aspects of capacity, ability and willingness.

Let’s now consider the second definition: “The possession of control or command over others.”

This is a commonplace understanding and usage of the term power. But the definition prompts the question: “The possession of control or command over others for what purpose?”

This second kind of power is wielded in order to motivate an individual or collective to do something, or not do something, to the benefit of the person, group or institution wielding the power.

Power is exercised, an action ensues or is halted, and the power exerciser gains benefit (value). Definition 2 power is therefore a distorted form of definition 1 power, which is neutral.

The concept of power is meaningless without an explicit or implied purpose. Whenever we encounter the term, we must ask: “in order to accomplish what?”

I therefore propose adopting this working definition of power for the remainder of the article:

Power is the capability of accomplishing something, with or without the use of coercion, for the benefit of oneself, others, or both.

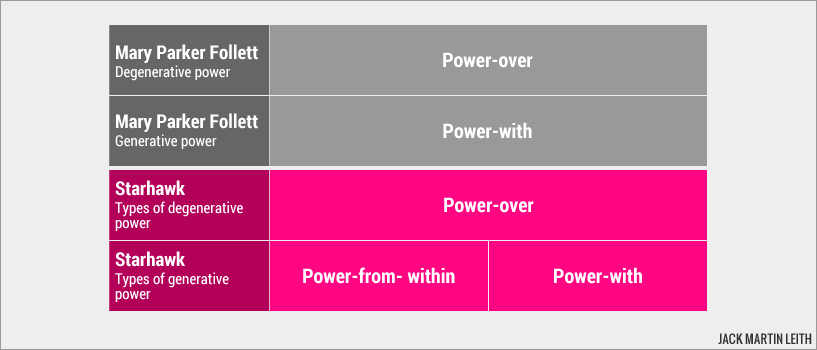

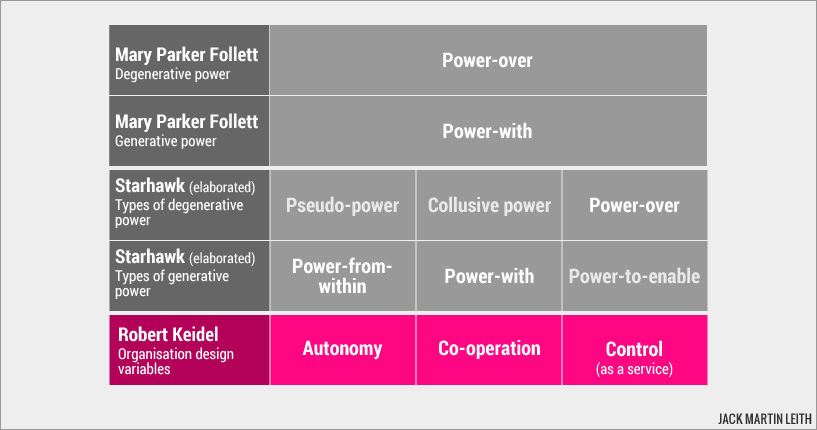

Mary Parker Follett’s two types of power (early 1900s)

Mary Parker Follett (1868–1933) was an American social worker, management consultant and philosopher, and a pioneer in the fields of organisational theory and organisational behaviour. She has been called “the mother of modern management.” (Source: Wikipedia.)

Mary Parker Follett originated the distinctions of power-over (coercive or oppressive power) and power-with (collaborative power). Cat Swetel claims (view source) that Follett identified a third kind of power, power-to, defined as “the power we have to create new things”. However, I can find no mention of this beyond Swetel’s article.

“Power is one of the key ideas in management, and so is the concept of authority. However, most studies on power are rather instrumental, dealing with the place of power in management, and how to achieve it. Less attention has been paid to the essential concepts of power and authority themselves in management thought and how they have evolved. To clarify these concepts, and to better understand the notions of power and authority in management and their proper use in organisations, this paper goes back to one of the pioneers in management thought: Mary Parker Follett (1868-1933). She had an original vision of power, holding that genuine power is not ‘power-over’, but ‘power-with.’”

Source: Power, Freedom and Authority in Management: Mary Parker Follett’s ‘Power-With’ by Domènec Melé & Josep M. Rosanas, Philosophy of Management, volume 3, pages 35–46 (2003) | My emphasis

Starhawk’s three types of power (1991)

Click on image or here to order a copy of the book from Amazon.co.uk

Starhawk (born Miriam Simos) is an American writer, teacher and activist, best known as a theorist of feminist neopaganism and ecofeminism. Her book The Spiral Dance was one of the main inspirations behind the Goddess movement. In 2013, she was listed in Watkins’ Mind Body Spirit magazine as one of the 100 Most Spiritually Influential Living People. (Source: Wikipedia.)In her third book, Truth or Dare: Encounters with Power, Authority, and Mystery, she reprises (without credit) Mary Parker Follett’s distinctions of power-over and power-with, adding a third distinction: power-from-within.

Power-from-within is linked to the mysteries that awaken our deepest abilities and potential.

Power-with is social power, the influence we wield among equals.

Power-over is linked to domination and control.Source: The Three Types of Power: an excerpt from Truth or Dare by Starhawk.

Rectifying the flaw in Starhawk’s power model

Starhawk contrasts power-over with power-with and power-from-within in a way that reflects old-school feminist ideology. Power-over is bad power. It is exercised predominantly by men, the misogynistic patriarchy, in order to oppress women. Power-with is good power, likewise power-from-within. These good forms of power are exercised mainly by women.

But Starhawk, whose books I have read and enjoyed, has made some fundamental errors, either deliberately or unintentionally.

- The degenerative form of power-with is not power-over. It is collusive power, where two or more people act together for self-serving or nefarious purposes.

- The degenerative form of power-from-within is not power-over. It is pseudo-power, often showing up as self-importance or bravado.

- The generative form of power-over is not power-with or power‑from‑within, but power‑to‑enable.

Power-over vs. power-to-enable

My working definition of power is “the capability of accomplishing something, with or without the use of coercion, for the benefit of oneself, others or both.”

Power-over can therefore be defined as “the capability of accomplishing something with the use of coercion for the benefit of oneself.”

And so its converse must be “the capability of accomplishing something without the use of coercion for the benefit of others.”

On this basis, we could refer to the generative form of power-over as altruistic (“showing unselfish concern for the welfare of others”) power. Instead, I’ve chosen to call it power-to-enable, for reasons that will become apparent when I introduce the work of Robert Keidel and John Heron in a few moments.

Power-over isn’t always about deliberately imposing one’s will on others and constraining their power-from-within. Sometimes it’s just a distorted form of power-to-enable, such as that displayed by an inept facilitator who sets the group a tightly-specified task, unwittingly closing-off creative possibilities and hindering the group’s progress towards its goals. No malice is intended.

Pseudo-power

Pseudo-power was prominent in the girl power movement that flourished during the 1990s. Sloganeering, bravado and ‘attitude’ were adopted as proxies for real autonomous power. A more recent example of the phenomenon is described by Jill P. Weber in Girl Power or Pseudo-Power? on the Psychology Today website.

Robert Keidel’s three organisational design variables (1995)

“People want power because they want autonomy.”

Source: Julie Beck, on The Atlantic (reporting on a study conducted by researchers from University of Cologne, University of Groningen, and Columbia University) | Read the article: People want power because they want autonomy by Julie Beck

Robert Keidel is Clinical Professor Emeritus at the LeBow College of Business, Drexel University, Philadelphia, USA.

In his insightful book, Seeing Organizational Patterns: A New Theory and Language of Organizational Design, he introduces an elegant model for improving the design of organisational systems in such areas as decision making, employee rewards and meeting management.

The central idea in the book is that an effective design must employ a judicious combination of three variables: autonomy, cooperation and control. Note that these labels are neutral and do not fall into the trap of thinking that autonomy and co‑operation are ‘good’, whereas control is ‘bad’.

The following graphic shows Keidel’s model applied to the design of decision systems, with the viable options indicated in blue type.

View an enlarged version of the Decision Systems example

When people encounter the word control, they tend to think about its degenerative form, which corresponds with power-over as defined by Starhawk and Mary Parker Follett. The autonomy of an individual, group or institution is being constrained or otherwise manipulated to the benefit of the individual, group or institution exercising control.

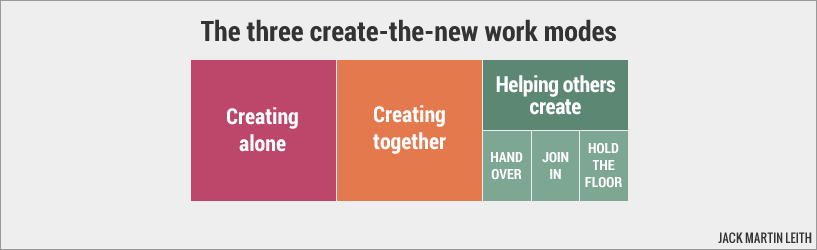

There is a benign, generative form of control I call control as a service. Examples include Houston Mission Control Center, air traffic control and railway signalling systems.In the military world, people began studying leadership a couple of thousand years ago — and interestingly, the military are less dismissive of management. Even more interestingly, they talk about something else we do not talk about in business at all. They have a third concept: command.

In military language, ‘command and control’ covers the various ways in which direction is given and the effects of actions are monitored. But in the language of business, ‘command and control’ has become shorthand for ‘authoritarian micro-management’, which is just one — usually dysfunctional — way, of exercising it. Giving the words ‘command and control’ this negative sense is a strange choice, because business is quite keen on ‘control’. Equating ‘command and control’ with ‘authoritarian micro-management’ is a category error — it confuses ‘fruit’ with ‘rotten apples’. Not using the word will not make the activity referred to as ‘command’ go away. NATO defines command as: ‘The authority invested in an individual for the direction, co-ordination and control of military forces’. Co-ordination and control are classic roles of management. So perhaps the bit we don’t feel so comfortable with is ‘direction’.

Command is something granted to someone by an external party. The external party confers rights of authority and along with them go responsibilities, duties and accountability. Responsibilities may be delegated or shared, but the commander remains accountable for the results. In the British Armed Forces, command is ultimately granted by the Sovereign: in the United States, by the President. In businesses it is granted by the owners of the business, who are most commonly the shareholders.

Command is as unavoidable in the business world as it is in the military one. Because it is a real requirement, somebody has got to do it, and because of its central importance in business we have to talk about it. So we do: we include it under ‘leadership’. As a result, we cause confusion.

Business thinking suffers from offering the simple duality of management and leadership, and the leadership literature contains futile debates because of a failure to distinguish leadership from command. There is a trinity of command, leadership and management, and both officers and executives have to practise all three, as illustrated [below].

The executive’s trinity: management, leadership – and command (pdf; 34pp) by Stephen Bungay, Ph.D., a director of Ashridge Strategic Management Centre

In the next image, you can see the relationship between Robert Keidel’s design variables and the power distinctions made by Starhawk and Mary Parker Follett. The thinking behind my elaboration of Starhawk’s power model should now be apparent.“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. This is the captain welcoming you aboard our flight to Chicago. We’re just completing the paperwork and we’ll be pushing back in a few minutes. I have to inform you that air traffic control has been abolished and that, as of today, planes will self-organise. My first officer and I will do our best to get you there safely and on time. Now fasten your seat belt, sit back, relax and enjoy the flight.”

Robert Keidel’s design variables suggest that if we want to conceive a new creation, bring it into existence and realise its value generation potential, then solo work and collaborative work are not alternatives — both are essential, and must be properly integrated. Further, some form of enabling function, such as a coach, facilitator, project leader, team leader or full-blown mission control function, needs to be in place.

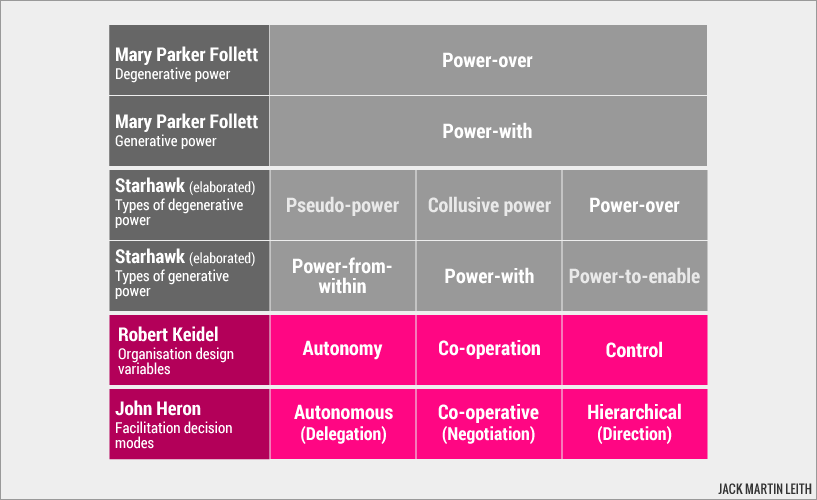

John Heron’s system of facilitation decision modes adds weight to this proposition.

Read more about control as a service

John Heron’s three facilitation decision modes (1999)

John Heron (1928–2022) was a psychologist, the originator of a participatory research method called co‑operative inquiry, and an eminent group facilitator and educator in the field of co‑counselling. In his final years, he was co-director of the South Pacific Centre for Human Inquiry, based in Auckland, New Zealand. He founded and ran the groundbreaking Human Potential Research Project (later, the Human Potential Research Group) at University of Surrey from 1970 to 1977, and was one of the founders in the UK of each of the following: Association of Humanistic Psychology Practitioners, Co‑counselling International, Institute for the Development of Human Potential, New Paradigm Research Group, and Research Council for Complementary Medicine. Source: Wikipedia.

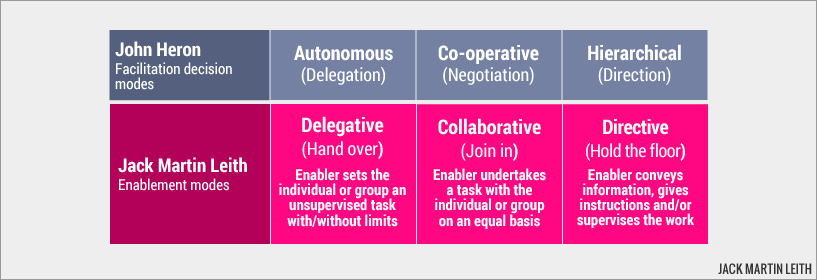

In The Complete Facilitator’s Handbook (pdf), John Heron describes the three decision modes available to facilitators: hierarchical (he also refers to this as direction), where the facilitator makes the decision for group members; co-operative (a.k.a. negotiation), where the facilitator reaches the decision with group members; and autonomous (a.k.a. delegation), where the facilitator hands over the decision-making process to group members. The labels are neutral, as is the case with Robert Keidel’s model.

The facilitator weaves the three modes into the design of a particular co-creation meeting and deploys all of them when facilitating the meeting, moving effortlessly between modes in response to unfolding circumstances, regardless of whether he or she is working one-to-one, with a small group, or with a large one.

Visit the John Heron Human Inquiry Archive, where you can download some of his works in their entirety“The hierarchical mode Here you, the facilitator, direct the learning process, exercise your power over it, and do things for the group. You lead from the front by thinking and acting on behalf of the group. You decide on the objectives and the programme, interpret and give meaning, challenge resistances, manage group feeling and emotion, provide structures for learning and honour the claims of authentic behaviour in the group. You take full responsibility, in charge of all major decisions on all dimensions of the learning process.

The co-operative mode Here you share your power over the learning process and manage the different dimensions with the group. You enable and guide the group to become more self-directing in the various forms of learning by conferring with them and prompting them. You work with group members to decide on the programme, to give meaning to experiences, to confront resistances, and so on. In this process, you share your own view which, though influential, is not final but one among many. Outcomes are always negotiated. You collaborate with the members of the group in devising the learning process: your facilitation is co-operative.

The autonomous mode Here you respect the total autonomy of the group: you do not do things for them, or with them, but give them freedom to find their own way, exercising their own judgment without any intervention on your part. Without any reminders, guidance or assistance, they evolve their programme, give meaning to what is going on, find ways of confronting their avoidances, and so on. The bedrock of learning is unprompted, self-directed practice, and here you delegate it to the learner and give space for it. This does not mean the abdication of responsibility. It is the subtle art of creating conditions within which people can exercise full self-determination in their learning.”

Source: John Heron, The Complete Facilitator’s Handbook (pdf; 428pp). He is talking about the facilitation of learning groups, but the three modes apply equally to action-focused groups.

Keidel – Heron correlation

The next graphic shows the strong correlation between John Heron’s facilitation decision modes and Robert Keidel’s organisation design variables.

Was John Heron influenced by Robert Keidel’s model? Seeing Organizational Patterns was published four years before The Complete Facilitator’s Handbook, so it’s possible, although Heron and Keidel inhabited very different worlds. My hope is that both men uncovered a universal truth independently of each other.

John Heron created the decision mode model for the benefit of facilitators, particularly those involved in developmental groupwork. But the model should be applied by all those engaged in catalysing and supporting create-the-new work, such as coaches, project leaders, team leaders and bosses.

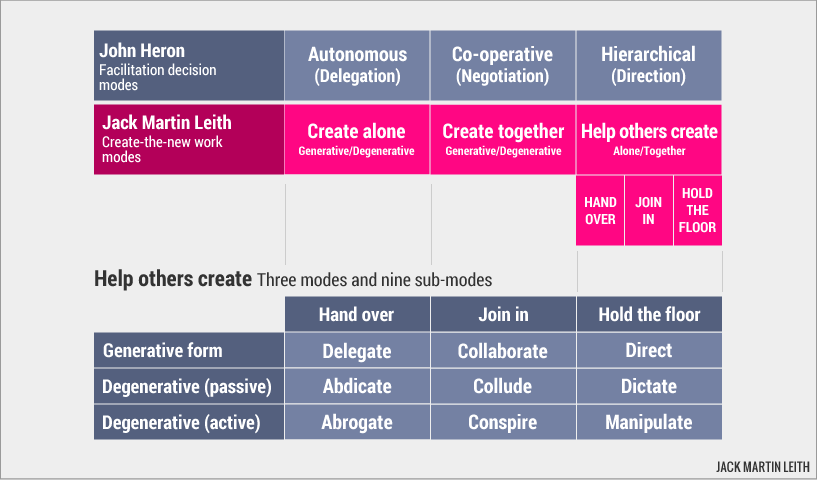

Jack Martin Leith’s three create-the-new work modes

I hope it’s now clear how I came to identify the three create-the-new ways of working and that you’re ready to explore each of them in more detail.

In the image below, you can select one of the 12 hotspots and jump down the page to read more.

Note that:

- Each way of working (create alone, create together, help others create) can have generative or degenerative consequences.

- ‘Help others create’ means helping someone create alone, as well as helping two or more people create together.

- ‘Help others create’ consists of three modes of enablement that correspond with John Heron’s facilitation decision modes: Delegate (corresponds with his autonomous mode), Collaborate (co-operative) and Direct (hierarchical).

Clicking on a word will take you to that section.

Clicking on a word will take you to that section.

Note that there are links back to this graphic throughout the remainder of the article.

Both authority and responsibility arise in the same moment — in that moment where some inner vision meets the world in a concrete action. Authority and responsibility are twins — born in the moment when we take the initiative.

I have authority over the thing I am authoring… As the author, I hold the vision. And I have a responsibility to that vision: to articulate and to act on that vision. Because no one else can. Authority and responsibility are the same size. I have responsibility for what I have authority for. I have authority for what I have responsibility for. Without responsibility, there is no authority.

Source: Clear Definitions #2: Responsibility, by Charles Davies.

Many writers, music composers and graphic designers create the new without any input from a collaborator. This website is all my own work, from writing the words and making the graphics to handling all the technical WordPress stuff. I am creating alone at this very moment.[Sinead] McKeefry creates mood boards when planning Winkleman’s outfits, and prefers to work alone when coming up with the concepts.

The Traitors: The stylist behind Claudia Winkleman’s tartan chic, on BBC News website

I will use creating an online article as an example of creating alone.

I am ‘creating, conceiving and bringing into being’ an online article, the primary purpose of which is to encourage people to employ the three create-the-new work modes and to understand the rationale for doing so.

One of the enduring myths in business management circles is that groups are a great source of creativity. However, this is counter to what researchers¹ have found: individuals, in fact, generate a much higher number of original ideas than groups.

Source: The problem with group mind, by Stowe Boyd.

1. Productivity Loss in Brainstorming Groups: A Meta-Analytic Integration, by Brian Mullen , Craig Johnson and Eduardo Salas, in Basic and Applied Social Psychology, Volume 12, 1991 – Issue 1 | View abstract / buy

See also Why Group Brainstorming Is a Waste of Time, by Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, on Harvard Business Review website.

Groups where conformity suppresses the generation of ideas have a tendency to produce, at best, barely adequate solutions, and, at worst, poor and predictable solutions. The best method is for each member of the group to spend significant time alone working on ideas, and for the group to assemble to discuss ideas these individuals have developed.

Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, Occasional Paper No.6—An Officer and a Problem Solver (via Ed Brimmer)

Upsides and generative consequences

Truly original and highly potent concepts can be produced.Without someone else in the room requiring my attention, I can get into a state of flow, access creative imagination (in contrast to synthetic imagination) and produce a one-of-a-kind article with the potential to generate significant downstream value.

Concept integrity is preserved.

By working alone, I have eliminated the possibility that one or more co-authors will want to dumb down my ideas, impose their own ideas, or insist on a compromise, each of which would result in an inferior article.

The concept has a surrogate parent.

If I should ever decide to turn the article into a book, I will take the role of adoptive parent until the finished product is available for purchase, speaking on its behalf and taking responsibility for its welfare.

Downsides and degenerative consequences

These are some of the undesirable consequences of this type of create-the-new work:Bold but unviable concepts are produced.

Without one or more co-authors to keep me in check, I could easily create an article featuring some potent ideas that defy the status quo and offer a truly new perspective, but that have very little prospect of adoption in the real world.

The new creation is stillborn.

Here, I decide to write an article about the three create-the-new work modes, but the writing task is overwhelming and, with no co-authors to share the burden and help me stay motivated, I wave the white flag and consign the half-written piece to the archives. This has happened more than once during the past decade when I failed to complete the article you are currently reading.

Value generation potential is never fully realised.

This is another state of affairs I know well. I write and publish an article that introduces some models and methods with real world potential. The article is well received, but instead of forming a group of collaborators to help me translate it into a book, a conference talk and a consulting offering, I shift my attention to the next writing project and value generation potential remains unrealised.

“In 1545, Jacopo da Pontormo scored a major commission from Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici to paint the main chapel of Florence’s church of San Lorenzo. A contemporary of masters like Michelangelo, Pontormo was a distinguished but aging artist who was eager to secure his legacy.

Pontormo knew he needed to make these frescoes the crowning achievement of his career, so he sealed off the entire chapel. He built walls, erected partitions, and hung blinds so that nobody could steal his ideas or sneak an early peek. Trusting no one, he chased away local youth and kept human contact to a minimum. He spent eleven years holed up, painting Christ on Judgement Day, Noah’s ark, and Creation itself.

Pontormo died before his work on the chapel was done, and none of it survives, but the legendary Renaissance writer Vasari visited the site soon after the painter’s death. He reported a confused composition and unsettling lack of alignment, scenes that ran into each other every which way. Robert Greene writes, ‘These frescoes were visual equivalents of the effects of isolation on the human mind: a loss of proportion, an obsession with detail combined with an inability to see the larger picture.’”

Source: Why Seclusion Is the Enemy of Creativity, by Eliot Peper, on Harvard Business Review

If I should ever decide to develop this article into a book, someone will need to edit the manuscript prior to publication, and many others will be involved in downstream activities, such as designing the book jacket, soliciting reviews, getting the book printed, doing the marketing, making social media posts (not my forte), organising book signing events, and the rest. It would be hard to find a single individual possessing all these capabilities.

In the workplace, a fair amount of create-the-new work is carried out in a group setting such as a Zoom call, face to face meeting or workshop. Management commentators such as Greg Satell (see here for example) sound loud warnings about the myth of the lone inventor, and in the wider world the terms ‘creating’ and ‘collaborating’ have become almost synonymous. But creating together has downsides as well as upsides, and eventual consequences can be generative, degenerative or both.

Upsides and generative consequences

Diverse views and talents are brought into play.Ken Blanchard, co-author of the One Minute Manager, captured the essence of this benefit of creating together when he said, “None of us is as smart as all of us.”

In a group setting, people pool their talents to challenge assumptions, eliminate flaws, make improvements, surmount obstacles and achieve goals, and to undertake the often laborious work needed to bring a create-the-new project to fruition.

People support and encourage each other.

Bringing the new into being can be a long and arduous process. Without sustained support and encouragement the project may hit the buffers.

Value generation potential is realised.

Realising the value generation potential of the new creation is usually best accomplished through good teamwork and effective collaboration with all those whose contribution, cooperation and consent are vital to the successful completion of the project.

Downsides and degenerative consequences

These are the main dangers:Lack of awareness that an idea is conceived in the mind of an individual.

Ideas arise from synthetic imagination, not creative imagination.

Creative imagination is more readily activated when working alone or in a two-person partnership.

Read about synthetic imagination and creative imagination

Groupthink arises, a collusion of mediocrity ensues and the status quo prevails.

View the Wikipedia entry for GroupthinkGroups are meant to be better decision-makers than individuals, because they combine many perspectives. But in practice, a group doesn’t base its decisions on the info specific to each member, but only on the info common to them all. This casts doubt on the idea that “two heads are better than one”, and helps explain why, despite popular wisdom, diversity generally does not make teams better.

Gurwinder Bhogal, , on UnHerd website

The link goes to this research paper: The relationship between team diversity and team performance: reconciling promise and reality through a comprehensive meta-analysis registered report, by Lukas Wallrich, Victoria Opara, Miki Wesolowska, Ditte Barnoth, and Sayeh Yousefi. The pdf document is not paywalled.

Read about The Collusion of Mediocrity

Here’s How to Spot Within 10 Minutes If Someone Has A Hidden Agenda, by Scott Mautz, on Inc.

In each of these cases, the level of potential downstream value is likely to be diminished.

Founders of many post-industrial companies are afraid of authority. They rightly don’t want to become the command-and-control dictators of the past. So they give up their authority, passing it to groups instead. It’s become a crime to talk about ‘I’ or ‘me’. Everything must be ‘we’ and ‘us’. A noble intention with disastrous consequences.

As well as removing the formal power and authority of one human being over another, these new organisational models have lost their connection to creative authority. That is, the authority to bring an individual’s creative vision to life. People are giving up their right to fully express themselves and live their personal calling in life. Instead they subjugate themselves to the group.

What’s happening here is the conflation of formal authority and creative authority. Formal authority can be stifling, but creative authority is the source of the passion in a company. There’s very little with more vitality than someone pursuing their vision — just watch an early stage start-up founder in action. But give it away and the energy begins to drain.

Source: Truly responsive organisations love authority, by Tom Nixon.

In the workplace, these are the principal roles concerned with helping others create:

- Facilitator

- Coach

- Thinking partner

- Project leader

- Team leader

- Line manager

- Consultant

There are three principal enablement modes, each corresponding with one of John Heron’s three facilitation decision modes. I’ve adopted new names for the modes to make them a good fit with other aspects of create-the-new work. Each mode applies equally to individual and group enablement.

In the passage appearing below, John Heron explains that, at a meta level, you will always be in directive mode. This is unavoidable, even for the facilitator of a participant-led Open Space meeting, who will have determined, without any input from the meeting participants, the thematic question, the number of rounds of self-managed sessions and their duration, and the overall timetable for the gathering.

The facilitator could hand over responsibility for making these decisions to the participants on their arrival at the venue. (This is not recommended as time-wasting chaos will ensue, which is why the facilitator makes these decisions in advance, as a service to the participant group.) However, he or she will still be doing so from a directive standpoint.

Flexibility in the use of decision-modes

I exercise unilateral political authority about learning when I take a meta-decision about whether to make decisions – for example about the programme of learning – hierarchically for the group, co-operatively with the group, or to delegate this decision-making to the group, or some combination of these. Even when I consult the group about whether to make planning decisions hierarchically, co-operatively or by delegation, I have still made, at a higher meta-level, a unilateral, hierarchical decision to do so. I have discussed this matter most thoroughly in Chapter 2 of The Complete Facilitator’s Handbook.

No facilitator can avoid the exercise of unilateral decision-making at these meta-levels. I make it clear at the start of a workshop what meta-decisions I have taken. I work with this most explicitly in a five day facilitation skills workshop. So I start the workshop proposing (i) that for the first day or so I will decide hierarchically on the training programme, both in order to present the trainees with issues which I think are fundamental, and in order to model such decision-making; (ii) that some time into day two or day three, I will shift over into co-operative decision-making to negotiate a contract between participants’ needs and interests and what I have on offer; and (iii) that on the last day or two we will have an autonomy lab, in which participants post up what they have to teach and what they want to learn, then everyone plans their own learning on a basis of self-direction and peer negotiation, and I will be a resource and learner alongside everyone else.

Source: John Heron, Helping whole people learn, Chapter 6 from Working with experience: animating learning, edited by David Boud and Nod Miller (1996).

Some ways of enabling

When working with individuals or groups

- Keeping an overview

- Providing guidance and support

- Challenging assumptions and limiting beliefs

- Creating a safe space

- Encouraging openness and candour

- Eliciting and maintaining focus on desired outcomes

- Alerting the individual or group to imminent jeopardy

- Galvanizing other(s) into sustained action

- Helping identify and remove constraints

- Detecting cognitive biases and flawed reasoning

- Giving honest feedback

- Addressing conflicts

- Being a witness

- Assisting in the acquisition of resources

- Championing possibility and greatness

When working with groups

- Establishing and maintaining mutual respect

- Ensuring that all voices are heard

- Banishing groupthink and collusions of mediocrity

If there is no designated facilitator in a group setting, it is possible that one group member will assume this role by stealth. These pseudo-facilitators may follow their own agendas and sidestep or overrule any objections, with degenerative consequences.

Each enablement mode has two degenerative, disabling counterparts that limit the amount of downstream value that potentially could be generated.

The passive form of disablement represents a ‘sin of omission’ on the part of the enabler. Associated behaviour is unintended, neglectful and exhibited without malicious intent. A moment of thoughtlessness, perhaps triggered by anxiety or overwhelm, can easily prompt an inexpedient action or thwart an expedient action, either of which may have degenerative consequences. Lack of expertise and limited experience can also contribute to unwanted results.

The active form of disablement represents a ‘sin of commission.’ Associated behaviour is deliberate and exhibited with malicious, even if unconscious, intent.

THE THREE ENABLEMENT MODES AND NINE SUB-MODES IN MORE DETAIL

Hand over

The enabler sets the individual or group an unsupervised task with or without limits.

The delegated task is either bounded (there is a brief of some kind) or unbounded (there is no brief but there may be a time limit or some other non-negotiable constraint).When a facilitator delegates a task and directs people to get on with it, group members might decide to work alone, or work together as equals, or let an elected or self-appointed leader direct their work, or use some combination of these.

Hand over | Sub-mode 1: Delegate

When working in the Delegate sub-mode, the enabler is required to:

- Specify completion time or date, and outcome requirements.

- Give clear guidance.

- Provide whatever resources may be needed.

- Trust the individual or group to complete the task successfully without supervision.

- Resit the urge to intervene.

- Keep progress monitoring to a minimum

- Stay in the background or leave the room, while remaining fully present and available to provide assistance if requested.

- Hold the space.

This is the stance adopted by facilitators of Open Space meetings during the self-managed breakout sessions.

Radical Delegation Framework, by Shreyas Doshi | X: @shreya | Exposition (video, 2:29)

Hand over | Sub-mode 2: Abdicate

Abdication is a failure or refusal to fulfil a duty or responsibility.

In this scenario, the enabler has ducked responsibility for helping the individual or group do the best work.

For example, he or she fails to provide a brief when one is needed, does not make essential resources available, is absent when guidance is required, or does not allow sufficient time for completion of the task.

I have been working with the Open Space format since 1988, just three years after its inception. An Open Space gathering can yield breakthrough results when the format is used in the right way, but the possibility of abdication on the part of the facilitator is apparent in the five Open Space principles:

- Whoever comes are the right people.

- Wherever it happens is the right place.

- Whenever it starts is the right time.

- Whatever happens is the only thing that could happen.

- When its over, its over.

If, at a one-day Open Space meeting, people have spent the morning discussing trivial issues and are set to do likewise throughout the afternoon, the facilitator is shirking responsibility if he or she fails to intervene on the basis that “whatever happens is the only thing that could happen.”

In this scenario, the facilitator must switch sub-modes from Delegate to Direct, call everyone to the agenda wall and ask, “Are you sure this is how you want to spend what’s left of your time together today?” Failure to take such action would represent abdication.

Hand over | Sub-mode 3: Abrogate

Abrogate means cancel, put an end to, render null and void, treat as non-existent. In a create-the-new context, it means thwart or limit a value generation possibility.

Imagine for a moment that a large-scale create-the-new meeting is in progress and breakout groups have just completed a task set by the facilitator. Any abrogative behaviour on the part of the facilitator is likely to nullify the fruits of people’s efforts and cancel-out any potential value their work might have generated downstream.

Here are some examples of abrogation in this kind of situation:

- Pretending to applaud the work produced while having no intention of taking it any further, or blatantly ignoring it.

- Being dismissive or damning with faint praise.

- Responding with a joke or a vainglorious anecdote.

- Setting up an individual or group to fail.

- Undermining someone’s confidence in their ability to achieve the desired result.

- Distorting or concealing information.

- Keeping people in their place.

Join in

The enabler undertakes a task with the individual or group on an equal footing.

Here you share your power over the learning process and manage the different dimensions with the group. You enable and guide the group to become more self-directing in the various forms of learning by conferring with them and prompting them. You work with group members to decide on the programme, to give meaning to experiences, to confront resistances, and so on. In this process, you share your own view which, though influential, is not final but one among many. Outcomes are always negotiated. You collaborate with the members of the group in devising the learning process: your facilitation is co-operative.

John Heron, describing the co-operative facilitation mode

Join in | Sub-mode 1: Collaborate

In the 1990s, it was common practice for a facilitator to establish the ground rules at the start of a workshop. Rather than impose these rules, the facilitator would take a fresh sheet of flipchart paper and work with the group to create a set of principles that everyone, including the facilitator, was willing and able to uphold.

When i was facilitating this kind of process, “no bad language” would commonly be proposed, and I would always exclude it on the basis that the occasional expletive might pass my lips, particularly when trying hard to suppress it. This is a good example of an enabler working in the Collaborate sub-mode. He or she is part of the group, working with people an equal footing.

Operating in this sub-mode can include active participation in group activities. In an Open Space meeting, for example, the facilitator might join a session or even offer to host one. Many Open Space practitioners would be shocked by this suggestion, considering it a contravention of the Open Space facilitation code.

But if the facilitator is in possession of specialist knowledge that might benefit the group, then he or she has a responsibility to provide it. Failure to do so would be an act of abrogation. Of course, discernment is essential and egotistic action must be avoided.

Join in | Sub-mode 2: Collude

Therefore, in the context of helping others create, collusion is the process in which a facilitator, coach or other enabler consciously or unconsciously participates with an individual or group to avoid an issue that needs to be addressed, thereby avoiding discomfort.In psychotherapy, collusion is the process in which a therapist consciously or nonconsciously participates with a client or third party to avoid an issue that needs to be addressed.

Source: APA Dictionary of Psychology (view).

Here are some common examples of collusion when an enabler is in working with an individual or group on an equal footing:

- Not challenging assumptions and limiting beliefs.

- Not pointing to the elephant in the room.

- Allowing the individual or group to lose focus on desired outcomes.

- Not warning about imminent jeopardy.

- Allowing necessary action to be deferred or avoided.

- Failing to point out show-stopping constraints that are being ignored.

- Not exposing cognitive biases and flawed reasoning.

- Failing to give honest feedback.

- Not addressing conflicts.

- Allowing mediocre outputs to be taken forward.

- Allowing disrespectful or dismissive comments, or bigoted/racist/sexist remarks, to go unchallenged.

- Allowing the individual or group to be swamped by trivial details, ignoring the big picture.

- Letting voices go unheard.

- Allowing groupthink to prevail.

- Displaying approval-seeking behaviour.

Read about The Collusion of Mediocrity by Paul Levy, who has written extensively on the topic

Paul Levy: Revisiting the Collusion of Mediocrity in 2019 (7:03)

Read the article: 12 Ways To Avoid Collusion In The Coaching Relationship, by Michael Arloski, Ph.D., on Health and Wellness Coaching websiteJoin in | Sub-mode 3: Conspire

Someone working in the Conspire sub-mode seeks to co-opt the individual or group for his or her own nefarious purposes. He or she may do this brazenly or, more likely, covertly.

The Gunpowder Plot

Conspiratorial action does not occur unwittingly. There is conscious intent to halt current value generation, prevent or diminish future value generation, or generate anti-value either in the present or in the future.Hold the floor

The enabler conveys information, gives instructions and/or supervises the work.

When you are working with an individual or group and holding the floor, be aware that you are there at the explicit or tacit invitation of the other party. You have been given a permit to make decisions on their behalf, and this can be withdrawn at any moment.On three unconnected occasions, while running workshops for corporate clients, the participants declared UDI and the facilitation team was asked us to leave the room. In each of these instances, we were delighted that the group was taking responsibility for its collective work. My colleagues and I simply took an extended break until we were invited back.Europe’s kings and queens usually learned, sometimes the hard way, that the exercise of power depends on popular consent.

Source: Reflections on the non-revolution, by Ian Leslie, in The Ruffian newsletter.

Hold the floor | Sub-mode 1: Direct

In this sub-mode, directing is not an authoritarian act. It’s a form of enablement.

When I give directions to a tourist who asks to be shown the way to the railway station, I’m not exercising power-over; I’m providing a service. He or she is free to ignore my directions.

A movie made without a director would be a disaster. The director serves the actors, the scene, the finished product and the audience members who will watch it.

An orchestra without a conductor is unlikely to be worth listening to.

Throughout the briefing and agenda creation session of an Open Space meeting, the facilitator is operating in the Direct sub-mode.

This is not the time for autonomy or collaboration. The participants need essential information, clear instructions and an efficient process by which sessions are proposed and the agenda is finalised (for the time being at least) with minimum fuss, confusion and time consumption.

Once that work is complete and the self-managed breakout sessions begin, the facilitator moves into the Delegate sub-mode until the whole group reconvenes for the closing session, when he or she resumes a directive stance.

Control as a service

In the earlier section about Robert Keidel’s organisation design variables, I mentioned control as a service and gave the example of air traffic control, without which air travel would not be possible.

The concepts of self-organisation and self-management² are gradually moving from the fringes into the mainstream, packaged and branded in various ways, notably Teal organisations, Agile, Sociocracy and Holacracy®. Each of these approaches achieves a high score on the collaboration scale and a lower score on the autonomy scale, but registers little or nothing on the direction scale.

2. Read the article The Difference between Self-Management and Self-Organization, by Mario Moreira, on his Agile Adoption Roadmap website

Railway signalling centre, Network Rail, UK

I’ve been a vocal advocate of self-organisation and self-management since discovering Open Space in 1988, and have sought, as best I can, to help people free themselves from the tyranny of command and control.But I’ve noticed that many self-management evangelists have thrown out the baby with the bathwater. They fail to recognise the value to be gained from some form of ‘mission control’ function, even if it is composed of very few people.

The entity I have in mind has more power (of the enabling kind) than a project or programme management office. It is led by the project or programme director and is mandated to make course-correcting interventions.

These are some of the advantages of such an entity:

- Seeing the big picture, noticing dependencies and resolving any disconnects.

- Acting as a tracking station and seing to it that everyone is aware of what’s coming over the hill.

- Coordinating constituent projects in order to make best use of resources, prevent duplication of effort, plug any gaps and ensuring cohesion.

- Monitoring developments and performing a troubleshooting role, only intervening when absolutely necessary. Interventions are co-designed, not imposed — see The Tell–Sell–Test–Consult–Co-create model.

Hold the floor | Sub-mode 2: Dictate

Acting in a dictatorial manner means imposing your will on others and operating in an autocratic, high-handed, domineering way. This is the ‘power over’ mode described by Starhawk.

Facilitators, coaches and other enablers can easily slip into the Dictate sub-mode when feeling out of their depth. The difference between the Direct and Dictate sub-modes is very subtle, and any slippage is often a blip rather than a persistent modus operandi.

Dictatorial behaviour may be a distorted form of enablement rather than the act of a control freak. But even a momentary lapse can elicit passivity, dependence, reluctance to participate, hostility, withdrawal or rebellion.

“In my corporate life, I had taken part in many facilitated workshops over the years and had by and large found them to be ghastly affairs. The professional facilitators would be far too controlling, far too smug and always seemed to love the sound of their own voice. OK, not all, but far too many.”

David Gurteen, originator of the Knowledge Cafe format, on his Conversational Leadership website (view)

Hold the floor | Sub-mode 3: Manipulate

A person operating in the Manipulate sub-mode has a private agenda and malicious intent, and employs all manner of tricks and strategies in order to produce his or her desired outcome.

[Facipulation is] a mix of facilitation and manipulation, in which the leaders of a discussion seek to influence the course of that discussion by indirectly promoting particular lines of thought. The verb originated in the US in the 1980s and has become more popular in the last 10 years.Many change programs feature workshops, the stated purpose of which is to engage people around a particular course of action. These workshops often feature lots of time for open discussion, ostensibly to give people the opportunity to ‘get engaged’. Many of these forums are however monologic. It looks like facilitation, it sounds like facilitation, it may even feel like facilitation, but in fact the facilitator is pre-committed to a particular point of view.

Source: The day I got facipulated, by Paul Lawrence, principal at Centre for Coaching in Organisations, on Medium.

Go to the interactive graphicThe authoritarian personality favours clever manipulations and conspiracies.

Martin Gurri in Why all this Trump hysteria? on UnHerd

Martin Gurri is a former CIA analyst and the author of The Revolt of the Public.

In summary

When creating alone

![]() Remember the Jacopo da Pontormo story.

Remember the Jacopo da Pontormo story.

![]() Bring in a coach to support you in your solo work.

Bring in a coach to support you in your solo work.

![]() Form a team to help you mature your concept, bring it to life and realise its value generation potential.

Form a team to help you mature your concept, bring it to life and realise its value generation potential.

When creating together

![]() Adopt practices that enable people to work alone, in pairs and in groups.

Adopt practices that enable people to work alone, in pairs and in groups.

![]() Know how to combine the three kinds of create-the-new work.

Know how to combine the three kinds of create-the-new work.

![]() Bring in a coach or a facilitator to support the collaborative work.

Bring in a coach or a facilitator to support the collaborative work.

When helping others create

![]() Make sure you are equally strong in all three enablement modes: hand over, join in, and hold the floor.

Make sure you are equally strong in all three enablement modes: hand over, join in, and hold the floor.

![]() Become adept at moving fluidly between enablement modes.

Become adept at moving fluidly between enablement modes.

![]() Maintain vigilance to avoid slipping into the degenerative forms of the modes.

Maintain vigilance to avoid slipping into the degenerative forms of the modes.

More quotes

Active and directed dissent is a better way to counter the cognitive biases of groups and individuals, and to sidestep groupthink. This is essential to increased innovation and creativity truly driving business.

Source: A Manifesto For A New Way Of Work, by Stowe Boyd

Where does individual power come from? It comes from the creative urge, the creative impulse. This is deeper than the notion of solving problems. It’s deeper than mechanical resolutions.

Source: What motivates people to take action? by Jon Rappoport

Innovation takes more than having ideas and expecting others to immediately accept them. If your idea is important enough, then it is your job to take responsibility for it and see it through.

The Semmelweis Myth And Why It’s Not Really True, by Greg Satell, on Medium

And the trouble with power is that it’s only as good as the wisdom of the person who wields it.

Left-brain thinking will destroy civilisation | Iain McGilchrist in conversation with Freddie Sayers, editor of UnHerd, on UnHerd website

Power is at the heart of this world, not because the world is evil but because marshaling energy to make a better reality takes power. What I’m talking about here is unlimited in terms of space and time. This is not some little parochial dark power a fool uses to provoke fear. This is not a pond. This is the ocean. This is the big one. This is what is at the core of the individual. It is not neutral, it is not empty, it is not a system, it is not technical. It is electric and alive. To put it another way, it is what you find inside the nut when you crack open the shell. You find the kernel. It says, ‘When you tap me, I give you energy, as much as you want.’ However, for this to happen, the decks need to be cleared of certain obstructions. Certain roadblocks need to be pushed out of the way. This can be done.

Source: Jon Rappoport

Continue reading

External websites

Brainstorming Doesn’t Work — Do This Instead, by Rochelle Bailis, on Forbes website

Collaborating Isn’t the Only Option, by Adam Kahane, on strategy+business website

The Difference between Self-Management and Self-Organization, by Mario Moreira, on his Agile Adoption Roadmap website

Girl Power or Pseudo-Power? by Jill P. Weber, on Psychology Today website

Hierarchy or Anarchy: Holarchical Structures and 3D Management, by Marco Antonio Robledo, Professor of Management, University of the Balearics Islands, Spain, on Enlivening Edge website

The need for facilitation, by Daniel Christian Wahl, on Medium

No bosses, no managers: the truth behind the ‘flat hierarchy’ facade, by André Spicer, on The Guardian website

People Want Power Because They Want Autonomy, by Julie Beck, reporting on a study conducted by researchers from University of Cologne, University of Groningen, and Columbia University, on The Atlantic website

Power is Returning to the Source, by Umair Haque, on Medium website

Problem-solving techniques take on new twist. For best solutions, intermittent collaboration provides the right formula, says Ethan Bernstein, an Associate Professor at Harvard Business School

Pseudo-power, by Scott Noelle, on EnjoyParenting.com website

Really Big Picture Enterprise Architecture: On power and gender, by Tom Graves

The Truth About Collaboration, by Gunther Sonnenfeld, on Medium website

What is power, anyway? by Tom Graves, Tetradian, on Slideshare

This website

How to modify co-creation meeting formats in order to honour the Max4 Principle

How Newcreators use mind, body and spirit to create the new and enrich the world

The Max4 Principle | The maximum group size for a proper conversation is four

How does Newcreate compare with design thinking?

How to put Newcreate into practice

Index to entire site (60+ pages)

Search the site

Not case sensitive. Do not to hit return.